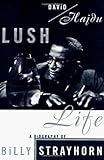

David Hadju. Lush Life: A Biography of Billy Strayhorn. New York: William Morrow and Company, 1996. xii + 305 pp. $27.50 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-374-19438-3.

Reviewed by Frank Salamone (Iona College)

Published on H-PCAACA (September, 1996)

David Hadju, like many others who write about jazz, seems to think that, in order to enhance the subject of "his" study, he needs to attack the reputation of a "giant." In graduate school, I had a professor who scorned the actions of what he termed these Davids who seek to make their reputations by attacking Goliaths. Since the biggest giant in jazz is probably Duke Ellington, the Duke has come in for his fair share of attackers. After all is said and done, he still appears as a giant.

That statement, however, in no way seeks to diminish the reputation of Billy Strayhorn. "Strays" or "Swee' Pea" was a remarkably talented individual. He was a composer of note--"A Train," Lush Life" and others, a great arranger, and a perfect collaborator for Ellington. He did not live out his life in near-obscurity, as Hadju claims. In fact, as Hadju's own work demonstrates, The Duke Ellington Society asked Strayhorn to perform at its first concert. Ellington fans always knew how important Strayhorn was to Ellington. Indeed, this book almost diminishes his importance by pointing out how often Strayhorn was not with Duke!

Fortunately, real Ellington fans know that Ellington frequently stirred up mixed feelings among his band members. Many left him only to return. None, except perhaps Clark Terry a star trumpet player, ever sounded quite so good without him. Even Terry frequently returned to Duke for guest appearances. Ellington simply knew how to make those around him sound good. He stimulated maximum effort from his men and expected them to be adults and make use of the opportunities he presented.

Strayhorn simply did not have Ellington's drive. So what? Few mortals do. The fact that he was gay is used by Hadju as an explanation of his desire to stay in the shadows but Strays was openly gay. It was never a secret. It didn't matter to Ellington nor to Lena Horne who loved him and promoted his career. It didn't matter to Ben Webster or other of Duke's macho musicians. Hadju, in fact, fails in describing the New York gay scene in any convincing detail.

Certainly, Strayhorn was also Black but that, too, hardly explains his failure to drive himself. Duke was Black and drove himself. Indeed, Hadju notes that Strayhorn often noted how little prejudice he encountered in growing up in Pittsburgh--and "some of his best friends were white!" Like Ellington he was proud to be Black, knew Black culture, and liked people for how they treated him.

It's also true that Strayhorn loved and used classical music. That he did not pursue it as a career was not due to being Black. His favorite teacher at the conservatory died and he quit. Quitting was part of Strays' life and that had nothing to do with Ellington. The opportunity was there for him to use free time to develop his own projects. He did in fact do so but often failed to copyright his material or develop his annual Copasetic programs for a wider audience.

Hadju charges Ellington with stifling Strayhorn's career. Certainly, Duke did not want to lose Strayhorn. He did try to keep him from certain jobs. But he did that to others. Generally, according to Clark Terry, he kept people to him with ties of silk. He paid all of Strayhorn's bills, gave him free time to develop projects, was generous in praise, and made his own son, Mercer, jealous because of his treatment of Strayhorn.

I remember the album Ellington made, And His Mother Called Him Bill, on the occasion of Strayhorn's death. At the end of the album there is an unscripted moment. Ellington is doodling at the piano as his men pack their instruments. The style is like Strayhorn's and the tune is heart-wrenching. Ellington did not know he was being recorded and played a private tribute to Swee' Pea. Tears fell freely when I first heard the record. They still dribble now and then. That, for me, sums up their relationship.

To be fair, Hadju shares a vignette similar in tone. He mentions the first anniversary of Strayhorn's death. People gathered at the boat dock off the Henry Hudson Parkway in Manhattan. Someone asked why so many people were there. People asked the questioner why and he stated that earlier that day a tall, distinguished man had walked along the river with tears in his eyes and his head lowered. The Duke had paid his tribute in his own way that day.

Unfortunately, this book is only a start in understanding the complex relationship between two significant jazz figures. It does not really help us to understand either man, much less their relationship. Let us hope others build on Hadju's work.

This review is copyrighted (c) 1996 by H-Net and the Popular Culture and the American Culture Associations. It may be reproduced electronically for educational or scholarly use. The Associations reserve print rights and permissions. (Contact: P.C.Rollins at the following electronic address: Rollins@osuunx.ucc.okstate.edu)

If there is additional discussion of this review, you may access it through the network, at: https://networks.h-net.org/h-pcaaca.

Citation:

Frank Salamone. Review of Hadju, David, Lush Life: A Biography of Billy Strayhorn.

H-PCAACA, H-Net Reviews.

September, 1996.

URL: http://www.h-net.org/reviews/showrev.php?id=622

Copyright © 1996 by H-Net and the Popular Culture and the American Culture Associations, all rights reserved. H-Net permits the redistribution and reprinting of this work for nonprofit, educational purposes, with full and accurate attribution to the author, web location, date of publication, originating list, and H-Net: Humanities & Social Sciences Online. For any other proposed use, contact P.C. Rollins at Rollins@osuunx.ucc.okstate.edu or the Reviews editorial staff at hbooks@mail.h-net.org.